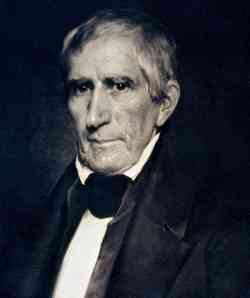

William Henry Harrison |

|

|---|---|

| Born | 2/9/1773 in Charles City County, Colony of Virginia |

| Died | 4/4/1841 in Washington, D.C. |

Biography |

|

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773 – April 4, 1841) was the ninth President of the United States, an American military officer and politician, and the first president to die in office. The oldest president elected until Ronald Reagan in 1980, and last President to be born before the United States Declaration of Independence, Harrison died on his thirty-second day in office of complications from a cold – the shortest tenure in United States presidential history. His death sparked a brief constitutional crisis, but that crisis ultimately resolved many questions about presidential succession left unanswered by the Constitution until passage of the 25th Amendment. Before election as president, Harrison served as the first territorial congressional delegate from the Northwest Territory, governor of the Indiana Territory and later as a U.S. representative and senator from Ohio. He originally gained national fame for leading U.S. forces against American Indians at the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811, where he earned the nickname "Tippecanoe" (or "Old Tippecanoe"). As a general in the subsequent War of 1812, his most notable contribution was a victory at the Battle of the Thames in 1813, which brought an end to hostilities in his region. After the war, Harrison moved to Ohio, where he was elected to the United States Congress, and in 1824 he became a member of the Senate. There he served a truncated term before being appointed as Minister Plenipotentiary to Colombia in May 1828. In Colombia, he lectured Simon Bolívar on the finer points of democracy before returning to his farm in Ohio, where he lived in relative retirement until he was nominated for the presidency in 1836. Defeated, he retired again to his farm before being elected president in 1840. Early lifeFamily background and childhoodHarrison was born into the prominent Harrison political family on the Berkeley Plantation in Charles City County, Virginia, on February 9, 1773; the youngest of Benjamin Harrison V and Elizabeth Bassett's seven children. He was the last president to be born a British subject before American Independence. His father was a Virginia planter and a delegate to the Continental Congress (1774–1777) who signed the Declaration of Independence and was governor of Virginia between 1781 and 1784. Harrison's brother, Carter Bassett Harrison, became a representative of Virginia in the United States House of Representatives, and Harrison's father-in-law was Representative John Cleves Symmes. Harrison's stepmother-in-law was the daughter of New Jersey Governor William Livingston.In 1787, at the age of 14, Harrison entered the Presbyterian Hampden-Sydney College. He attended the school until 1790, becoming well-versed in Latin and basic French. He was removed by his Episcopalian father, possibly because of a religious revival occurring at the school. He then briefly attended an academy in Southampton County before being again moved to Richmond where he began the study of medicine. He allegedly became involved with the antislavery Quakers and Methodists at the school, angering his pro-slavery father who again moved him to Philadelphia to board with Robert Morris, probably because of medical training available there. He entered the University of Pennsylvania in 1790 and there he continued to study medicine under Dr. Benjamin Rush. As Harrison explained to his biographer, he did not enjoy the subject. Shortly after he had arrived in Philadelphia in 1791, his father died, leaving him without funds for further schooling. He was 18 when his father died, and was left in the guardianship of Morris. Early military careerGovernor Henry Lee of Virginia, a friend of Harrison's father, learned of Harrison's impoverished situation after his father's death and persuaded him to join the army. Within 24 hours of meeting and discussing his future with Lee, Harrison was commissioned as an ensign in the U.S. Army, 11th U.S. Regt. of Infantry at the age of 18. He was first sent to Cincinnati in the Northwest Territory where the army was engaged in the ongoing Northwest Indian War. General "Mad Anthony" Wayne took command of the western army in 1792 following a disastrous defeat by its previous commander. Harrison was promoted to lieutenant that summer because of his strict attention to discipline, and the following year he was promoted to serve as aide-de-camp. It was from Wayne that Harrison learned how to successfully command an army on the American frontier. Harrison participated in Wayne's decisive victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794, which brought the Northwest Indian War to a successful close. After the war, Lieutenant Harrison was one of the signatories of the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, which opened much of present-day Ohio to settlement by Americans. Harrison's mother died in 1793 and he inherited a portion of the family's estate, including about 3,000 acres (12 km2) of land and several slaves. Harrison, who was still in the army at the time, sold his land to his brother. In 1795 Harrison met Anna Symmes, of North Bend, Ohio. She was the daughter of Judge John Cleves Symmes, a prominent figure in Ohio. When Harrison approached the Judge asking permission to marry Anna, he was refused. Harrison waited until the Judge left on business; he and Anna eloped and were married on November 25, 1795. After the marriage, the Judge was concerned about Harrison's ability to provide for Anna, and sold to the young couple 160 acres (65 ha) of land in North Bend. Together they had 10 children: six sons and four daughters. Nine lived into adulthood and one died in infancy. Although Anna was frequently in poor health during the marriage primarily due to her pregnancies, she outlived William by 23 years, dying at age 88 on February 25, 1864. Harrison resigned from the army in 1797 and began campaigning among his friends and family for a post in the Northwest Territorial government. With the aid of his close friend, Secretary of State Timothy Pickering, he was recommended to replace the outgoing Secretary of the Northwest Territory. He was appointed to the position, during which time he acted as governor during the frequent absences of Governor Arthur St. Clair. Member of CongressHarrison had many friends in the elite eastern social circles, and quickly gained a reputation among them as a frontier leader. Harrison ran a successful horse breeding enterprise that won him acclaim throughout the Northwest Territory. He championed the northwesterners' primary concern at the time: land prices, increasing his popularity. The United States Congress had put in place a land policy in the territory that led to high land costs that was disliked by many of the territory's citizens. When Harrison ran for Congress, he campaigned largely on working to alter the situation to help encourage immigration into the territory. In 1799, at age 26, Harrison defeated the son of Arthur St. Clair and was elected as the first delegate representing the Northwest Territory in the Sixth United States Congress, serving from March 4, 1799, to May 14, 1800. As a delegate from a territory, not a state, he had no authority to vote on bills but was permitted to serve on a committee, submit legislation, and debate.As delegate, Harrison successfully promoted the passage of the Harrison Land Act, which made it easier for the average settler to buy land in the Northwest Territory by allowing land to be sold in small tracts. This sudden availability of inexpensive land was an important factor in the rapid population growth of the Northwest Territory. Harrison also served on the committee that decided how to divide the Northwest Territory. The committee recommended splitting the territory into two segments, creating the Ohio Territory and the Indiana Territory. The bill passed and the two new territories were established in 1800. Without informing Harrison, President John Adams nominated him to become governor of the new territory due to ties to the west and his seemingly neutral political stances. He was confirmed by the Senate the following day. Harrison was caught unaware and accepted the position only after receiving assurances from the Jeffersonians that he would not be removed from office after they gained power in the upcoming elections. He then resigned from Congress. The Indiana Territory consisted of the future states of Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin and the eastern portion of Minnesota. GovernorHarrison moved to Vincennes, the capital of the new territory, on January 10, 1801. While in Vincennes, Harrison built a plantation style home he named Grouseland for its many birds. It was one of the first brick structures in the territory. The home, which has been restored and has become a popular modern tourist attraction, served as the center of social and political life in the territory. He also built a second home near Corydon, the second capital, at Harrison Valley. As governor, Harrison had wide ranging powers in the new territory, including the authority to appoint all territory officials and the territorial legislature and control over the division of the territory into districts. A primary responsibility was to obtain title to Native American lands to allow for white settlement to expand in the area, which enabled the region to eventually gain statehood. Harrison was also eager to expand the territory for personal reasons, as his own political fortunes were tied to Indiana's rise to statehood. In 1803 President Thomas Jefferson granted Harrison authority to negotiate and conclude treaties with the Indians. Harrison oversaw the creation of 13 treaties, buying more than 60,000,000 acres (240,000 km2) of land, including much of present day southern Indiana, from Native American leaders. The 1804 Treaty of St. Louis with Quashquame led to the surrender of much of western Illinois and parts of Missouri from the Sauk and Meskwaki. This treaty was greatly resented by the Sauk, especially Black Hawk, and was the primary reason many Sauk sided with Great Britain during the War of 1812. The Treaty of Grouseland in 1805 was thought by Harrison to have appeased Native Americans. Tensions remained high on the frontier and became much greater after the 1809 Treaty of Fort Wayne in which Harrison bought, by questionable means, more than 2,500,000 acres (10,000 km²) of land inhabited by Shawnee, Kickapoo, Wea, and Piankeshaw from the Miami tribe who claimed ownership of the land. Harrison rushed the process by offering large subsidies to the tribes and their leaders to have the treaty in place before President Jefferson left office. In 1803 Harrison lobbied Congress to repeal Article 6 of the Northwest Ordinance to permit slavery in the Indiana Territory. He claimed it was necessary to make the region more appealing to settlers and that it would ultimately make the territory economically viable. Congress suspended the article for 10 years, and the territories covered by the ordinance were granted the right to decide for themselves whether to permit slavery. That year Harrison had the appointed territorial legislature authorize indenturing. He then attempted to have slavery legalized outright, in both 1805 and 1807. This caused a significant stir in the territory. In 1809 the legislature was popularly elected for the first time and Harrison found himself at odds with the legislature when the abolitionist party came to power. They immediately blocked his plans for slavery and repealed the indenturing laws he had passed in 1803. Army generalTecumseh and TippecanoeAn Indian resistance movement against U.S. expansion had been growing around the Shawnee brothers Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa (The Prophet), which became known as Tecumseh's War. Tenskwatawa convinced the native tribes that they would be protected by the Great Spirit and no harm could befall them if they would rise up against the white settlers. He encouraged resistance by telling the tribes to only pay white traders half of what they owed and to give up all the white man's ways, including their clothing, whiskey, and muskets. In August 1810 Tecumseh and 400 armed warriors traveled down the Wabash River to meet with Harrison in Vincennes. The warriors were dressed in war paint, and their sudden appearance at first frightened the soldiers at Vincennes. The leaders of the group were escorted to Grouseland where they met Harrison. Tecumseh insisted that the Fort Wayne treaty was illegitimate and argued that no one tribe could sell land without the approval of the other tribes; he asked Harrison to nullify it and warned that Americans should not attempt to settle the lands sold in the treaty. Tecumseh informed Harrison that he had threatened to kill the chiefs who signed the treaty if they carried out its terms, and that his confederation of tribes was growing rapidly. Harrison responded by saying that the Miami were the owners of the land and could sell it if they so chose. He rejected Tecumseh's claim that all the Indians formed one nation, and told him that each tribe could have separate relations with the United States if they chose to. Harrison argued that the Great Spirit would have made all the tribes speak one language if they were to be one nation. Tecumseh launched an "impassioned rebuttal," but Harrison was unable to understand his language. A Shawnee who was friendly to Harrison cocked his pistol from the side lines to alert Harrison that Tecumseh's speech was leading to trouble; Tecumseh was encouraging the warriors to kill Harrison. Many of the warriors began to pull their weapons and Harrison pulled his sword. The entire town's population was only 1,000 and Tecumseh's men could have easily massacred the town, but once the few officers pulled their guns to defend Harrison the warriors backed down. Chief Winnemac, who was friendly to Harrison, countered Tecumseh's arguments to the warriors and instructed them that because they had come in peace, they should return home in peace. Before leaving, Tecumseh informed Harrison that unless the treaty was nullified, he would seek an alliance with the British. After the meeting, Tecumseh journeyed to meet with many of the tribes in the region, hoping to create a confederation with which to battle the Americans. In 1811, while Tecumseh was still away, Harrison was authorized by Secretary of War William Eustis to march against the nascent confederation as a show of force. Harrison moved north with an army of over 1,000 in an attempt to intimidate the Shawnee into making peace. The ploy failed, and the tribes launched a surprise attack on Harrison's army early on the morning of November 6 in what became known as the Battle of Tippecanoe. Harrison ultimately won his famous victory at what is now Prophetstown, Indiana, next to the Wabash and Tippecanoe Rivers. Harrison was hailed as a national hero although his troops had greatly outnumbered the attackers and had suffered many more casualties. In his initial report to Secretary Eustis, Harrison informed him of a battle having occurred near the Tippecanoe River, giving the battle its name, and that he feared an imminent reprisal attack. The first dispatch did not make clear which side had won the conflict, and the secretary at first interpreted it as a defeat. The follow-up dispatch made the American victory clear and the defeat of the Indians was more certain when no second attack occurred. Eustis replied with a lengthy note demanding to know why Harrison had not taken adequate precautions in fortifying his camp. Harrison responded that he considered the position strong enough not to require fortification. The dispute was the catalyst of a disagreement between Harrison and the Department of War that continued into the War of 1812. At first the newspapers did not carry any information about the battle to the public, instead covering the highlights of the ongoing Napoleonic Wars. One Ohio newspaper even printed a copy of the original dispatch and called the battle an American defeat. By December, most of the major American papers began to carry stories on the battle. Public outrage quickly grew and many Americans blamed the British for inciting the tribes to violence and supplying them with firearms. Acting on popular sentiment, Congress passed resolutions condemning the British for interfering in American domestic affairs. Tippecanoe fueled the worsening tension with Britain, culminating in a declaration of war only a few months later. War of 1812This portrait of Harrison originally showed him in civilian clothes as the congressional delegate from the Northwest Territory in 1800, but the uniform was added after he became famous in the War of 1812.The outbreak of war with the British in 1812 led to continued conflict with Native Americans in the Old Northwest, and Harrison remained in command of the army in Indiana. After the loss of Detroit, General James Winchester became the commander of the Army of the Northwest and Harrison was offered the rank of brigadier general, which he refused, desiring the sole command of the army. President James Madison removed Winchester and made Harrison the commander on September 17, 1812. Harrison inherited an army of fresh recruits, which he endeavored to drill. Initially he was greatly outnumbered and assumed a defensive posture. He constructed a defensive position at the Maumee rapids on the Maumee River in northwest Ohio in the winter of 1812-13. He named it Fort Meigs in honor of Ohio Govorner Return Jonathan Meigs Jr. After receiving reinforcements in 1813, he took the offensive, advancing the army farther north to battle the Indians and their new British allies. He won victories in Indiana and Ohio and recaptured Detroit, before invading Canada. He defeated the British at the Battle of the Thames, in which Tecumseh was killed. After the Battle of the Thames, Secretary of War John Armstrong divided the command of Harrison's army and assigned him to a backwater post and gave control of the front to one of Harrison's subordinates. Harrison had been having disagreements with Armstrong over the lack of coordination and effectiveness in the invasion of Canada. When Harrison was reassigned, he promptly resigned from the army to prevent what he called an act that was "subversive military order and discipline." His resignation was accepted in the summer of 1814. After the war ended, Congress investigated the circumstances of Harrison's resignation and decided that he had been mistreated by the Secretary of War during his campaign and that his resignation was justified. They awarded Harrison a gold medal for his services to the nation during the War of 1812. The Battle of the Thames was one of the great American victories in the war, second only to the Battle of New Orleans. PresidencyWhen Harrison came to Washington, he wanted to show that he was still the steadfast hero of Tippecanoe. He took the oath of office on March 4, 1841, a cold and wet day. Nevertheless, he faced the weather with neither his overcoat nor hat, and delivered the longest inaugural address in American history. At 8,444 words, it took nearly two hours to read, even after his friend and fellow Whig Daniel Webster had edited it for length. He then rode through the streets in the inaugural parade. The inaugural address was a detailed statement of the Whig agenda, essentially a repudiation of Jackson and Van Buren's policies. Harrison promised to reestablish the Bank of the United States and extend its capacity for credit by issuing paper currency (Henry Clay's American System); to defer to the judgment of Congress on legislative matters, with sparing use of his veto power; and to reverse Jackson's spoils system of executive patronage, which meant using the power of patronage to create a qualified staff, not to enhance his own standing in government. Clay, as leader of the Whigs and a powerful legislator (as well as a frustrated Presidential candidate in his own right), thus expected to have substantial influence in the Harrison administration, and subsequently ignored his own platform plank of overturning the Spoils system. Clay was a persistent interloper in Harrison's actions before and during his brief presidency, especially in putting forth his own preferences for Cabinet offices and other presidential appointments; Harrison rebuffed his aggression, saying "Mr. Clay, you forget that I am the President." The dispute intensified when Harrison named Daniel Webster, Clay's arch-rival for control of the Whig Party, his Secretary of State, and appeared to give Webster's supporters some highly coveted patronage positions; his sole concession to Clay was to name his protege, John J. Crittenden, to the post of Attorney General. When an unhappy Clay pressed Harrison on the appointments, tensions arose to such a point that Harrison ordered Clay not to visit the White House again, but to address the President only in writing. Despite this, the dispute continued until the president's death. Clay was not the only one who hoped to benefit from Harrison's election. Hordes of office applicants came to the White House, which was then open to all comers who wanted a meeting with the President. Most of his business during Harrison's month-long presidency involved heavy social obligations—an inevitable part of his high position and arrival in Washington—and receiving these visitors, who awaited him at all hours and filled the Executive Mansion. As he had with Clay, Harrison resisted pressure from other Whigs over patronage; when a group arrived in his office on March 16 to demand the removal of all Democrats from any appointed office, Harrison proclaimed, "So help me God, I will resign my office before I can be guilty of such an iniquity." Harrison's only official act of consequence was to call Congress into a special session. He and Henry Clay had disagreed over the necessity of such a session, and when in March 11 Harrison's cabinet proved evenly divided, the president vetoed the idea. A few days later, however, Treasury Secretary Thomas Ewing reported to Harrison that federal funds were in such trouble that the government could not continue to operate until Congress' regularly scheduled session in December; Harrison thus relented, and on March 17 proclaimed the special session in the interests of "the condition of the revenue and finance of the country." The session was scheduled to begin on May 31. |

|